Chapter One

‘Get down! Get down!’ Gruber said. His purple eyes glinted in the dark — and so did his red one. ‘They’ll see you. Keep out of sight until we land.’

Spich hid below the window of the spacecraft. His bright orange colouring was a total giveaway. The flashing lights on the ends of his wobbly antennae could be seen from a mile off.

Gruber was a lime green shade that was just as eye–boggling. Neither of them was suited to skulking in the shadows.

‘We can’t risk the Earthlings seeing us,’ Gruber grumbled, steering the spacecraft through the clear night sky. ‘Whatever will they think?’

Spich’s orange nose was flattened into the wall as he hid out of sight. ‘They’ll think we’re aliens,’ he said, speaking through his squashed nostrils.

‘But we are aliens,’ said Zzipa. His vibrant blue colouring glowed in the dark, so he’d worn a jumper to tone down the glare. He would have worn an anorak but he had a problem getting his bobbing antennae inside the hood. By the time he got his hood up and fiddled with the zips, the spacecraft would’ve arrived on planet Earth. Frankly, it wasn’t worth the effort.

‘That’s not the point,’ said Gruber. He brought the spacecraft down until it was just above the town’s tallest buildings. ‘We don’t want them knowing what we’re up to. We’d never hear the end of it.’

The silver spacecraft with its flashing blue and violet lights soared over the town at midnight like a sleek, shiny disc.

Zzipa gazed down at the view. ‘I can see lots of streetlights but hardly any people. Where do all the humans go to at night?’

‘They hide in their beds and go to sleep,’ said Gruber. ‘Goodness knows why they cover themselves in duvets. But that’s why we’re here — to learn all about their quirky ways.’

‘I’ve heard that some of them, especially children, check under their beds for monsters,’ said Spich. His lips curled into a smirk.

The others laughed.

‘I’ve never heard of anything so ridiculous,’ Gruber scoffed. ‘You don’t get monsters under the bed. Everyone knows they’re always in the wardrobe.’

The spacecraft suddenly lurched and altered direction, as if it knew where it was going better than Gruber did.

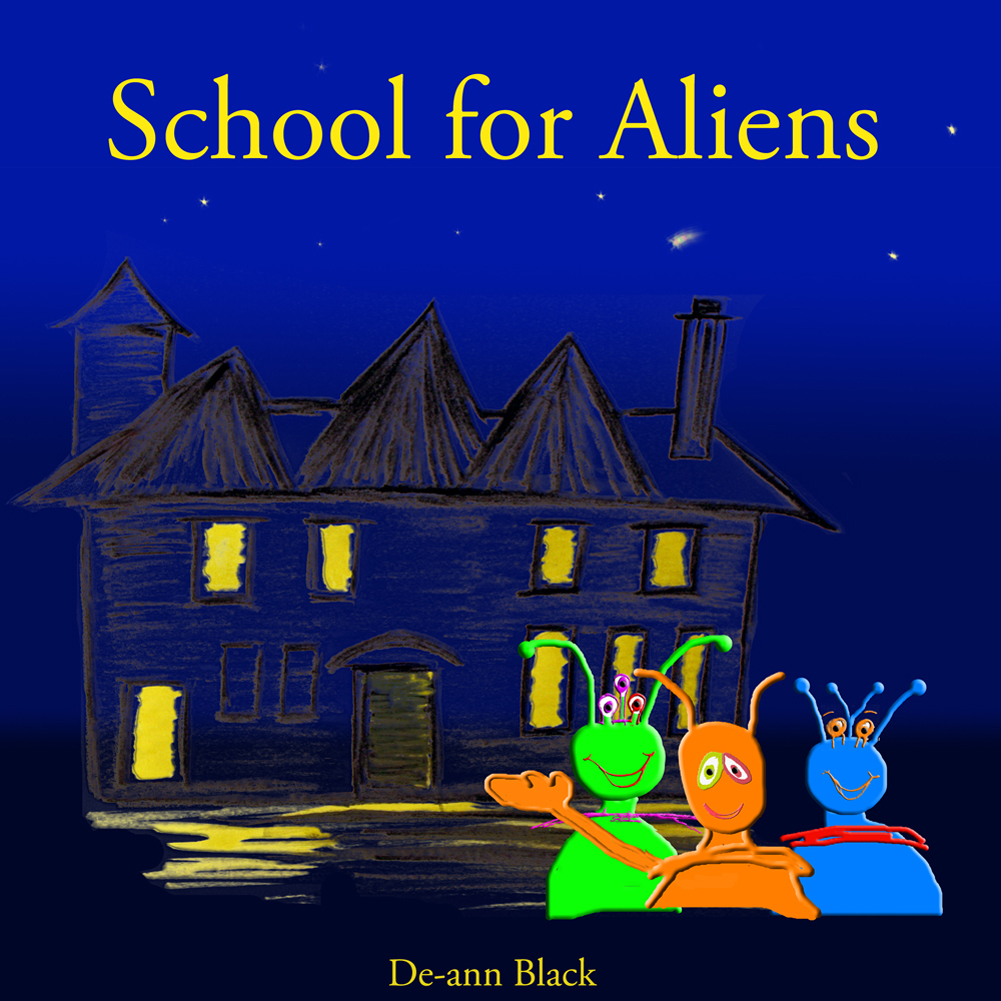

‘Ah, there’s the school now,’ Gruber said, looking down at the old brick building. The playing fields had dried out grass and a couple of spindly trees. No expense had been spared in making the aliens feel right at home.

A dim yellow light, barely worth having on because it was so dull, shone from one of the classrooms. The school hadn’t been used in years. It had been abandoned and left to rot where it stood on the outskirts of the town. A condemned notice was stuck to the front gates which were securely padlocked with a rusty chain. Gruber thought this was pointless. They didn’t need to lock out intruders. No one wanted to go near the rotten old school. No one except them. And they were only there as a last resort. Schools for aliens were thin on the ground. This was the only one on Earth, possibly even further.

The spacecraft did a spectacular landing in the playground. Spich hated the landings. The force as it hovered in the sky and then swooped down to the ground always made his stomach flip like a pancake. It made a loud whoosh as it landed (the spacecraft, not Spich’s stomach). He wished he hadn’t eaten his space snack of martian burgers and fizzy star juice. However, the journey from their planet, which was a zillion miles away from Earth, always gave him an appetite. Hic! And the fizz was making him hiccup.

The main doors of the spacecraft hissed open and around twenty aliens got out and went straight into the school.

Zzipa often wanted to take a look around the nearby streets, just to see what a human looked like in real life. He’d seen pictures of people of course, and scribbled drawings, but until his schooling was complete, he would not be allowed to actually meet one. But he lived in hope. Perhaps someday he’d be friends with an Earthling. Hopefully they’d be okay about him being blue, with boggling eyes that could look in every direction at the same time. And a smile that would frighten people at a single glance. Yes, it was a cheering thought.

Class had already started, which was fine, because alien schoolteachers had no idea of time. You sort of turned up when you needed to and left when you were ready. It worked for them. Perhaps if they’d been stricter it wouldn’t have taken an average of seventy years of school to learn the ways of humans.

Still, time was funny in space. Not funny in a giggle sense, funny as in weird. Whenever the aliens flew from their home planet, time hardly moved at all. Gruber checked his wrist watch. (Yes, aliens and humans did have a few things in common). It was just after midnight Earth time, but according to his watch they’d left their own planet at five minutes to six. If he’d been better at maths he’d have been able to work out whether this was fast or slow. Another twenty–one years of sums and he should be able to do it.

The class was filled to full capacity with a vast assortment of aliens. They were in every colour imaginable and a few shades that the human eye couldn’t detect. Two alien teachers, wearing suits and name badges, were at the front of the class. Henry Vermillion spoke to the pupils. He tapped his antenna on the board for attention.

‘Today’s lesson is — how to make raspberry pudding.’ Henry scribbled an outline of the dessert on the board.

‘Ahem!’ Bob Magenta, Henry’s assistant teacher, coughed, and glared at him with wide wiggling eyes.

Henry got the message. ‘I’ll eh…I’ll just check my notes,’ he said, flicking through the sheets of paper in his battered brown briefcase. ‘Ah yes, you’re right. I stand corrected. Got a little mixed up there with my geography.’ He shuffled the papers and started again. ‘Today’s lesson is the coast of Australia and other delightful locations.’ He pulled out a map of Antarctica, turned it every way possible, and then realised his mistake. After another rummage in his briefcase, he emerged triumphant with a knitting pattern.

‘Ahem!’ the assistant repeated.

Henry scrunched the knitting pattern into a papery ball and tucked it back into his briefcase. He decided to draw the coast of Australia on the board instead. He’d memorised it years ago and had the handy knack of being able to recall parts of it in fine detail. The most important parts were missing, but no one noticed. Then he scribbled a map of the local seaside coast of Britain which wasn’t far from the school. He took great pride in highlighting where he’d once gone paddling ankle deep in a rock pool.

The pupils were very impressed. So was Bob Magenta.

‘Did any Earthlings see you?’ said Bob.

‘No, no, well…maybe an old woman with a funny hat and a mad glint in her eye, but no one’s ever going to believe her.’

The lesson was a blur of activity, nonsense and wild guesses. Soon it was time for lunch. This was an experience in itself. Alien school dinners were a huge adventure. Definitely not for the faint–hearted or those who disliked things like macaroni cheese topped with rice pudding. It was also a bit of an embarrassment for Gruber, Spich and Zzipa. They’d chosen their new Earthling names from a list a few weeks ago when they’d started attending the school for aliens. Unfortunately the list was a takeaway menu and they’d named themselves Burger, Pizza and Chips. They’d used the names for over a week until someone explained their stupid mistake. To avoid looking like complete dimwits, they’d fibbed like mad. They said they’d chosen the names deliberately and intended mixing up the letters to make new names. And they did. Burger became Gruber, Pizza was now Zzipa and Chips became Spich.

‘Just ignore anyone who sneers at our names,’ Gruber said to Spich and Zzipa. They were queuing for large slices of slime and chocolate cake, a favourite with the aliens.

‘It’s not as if we’re the first to choose our names from a ridiculous Earthling list,’ said Spich. ‘Even our teachers got it stupidly wrong.’

This was true. Henry Vermillion and Bob Magenta had selected their surnames from a paint colour chart. They hadn’t bothered to jumble the letters around. They’d even managed to colour coordinate themselves. Henry was a vibrant red colour, just like his name, while Bob was a dull plumy brown.

Luckily everyone was too busy to notice Gruber, Spich and Zzipa. The school dining hall was a hive of activity with aliens queuing for food. The food was served up by three lilac dinner ladies from another planet. They were sloshing it out like lightning to keep up with demand.

Gruber was just about to munch into a savoury rissole when he saw a boy cycle past the window of the school dining hall. He almost dropped his lunch tray. ‘Did you see that?’ he mumbled, his mouth full of crumbs.

Spich squirted strawberry sauce on his fish fingers. ‘See what?’

‘A boy, about ten years old with floppy blond hair and a determined expression,’ Gruber said. ‘He went right past the window.’

They hurried over and peered through the glass into the darkness. Gruber put his lime green hands up to the window so he could see outside.

Zzipa was chewing on a flaky pastry. ‘I don’t see anyone,’ he said. Children were never out this late at night. He’d never seen anyone near the old school.

‘Maybe it was Tiddles,’ said Spich. Tiddles was the freaky–eyed cat who had stowed away on one of the spacecraft and made the school his new home. No one knew what planet he was from so they’d given him an Earthling name. Tiddles had orange and purple stripes from the tip of his tail to his neon whiskers. He also had an attitude problem and was often found meddling in things that were none of his business. The possibility that he’d have attempted to cycle a bike wasn’t entirely farfetched.

Suddenly, from out of the darkness, Gruber saw the boy again. ‘There he is!’ he shouted. ‘He’s peddling like mad across the playground.’

‘Gruber’s right,’ said Spich. ‘Whatever is the boy up to…?’